on charles ray and his archangel

The penchants of the art world can be frustratingly fickle. Only fifty years ago, money was poured into paintings of flat truth and ultimate shape. Now, the postmodernists have engendered truth from dead sheep in vitrine tanks. Now, minimalism and irony connote virtuosic depth. Figural representation has become traditional, and thus disavowed, as if all the mysteries of the human body had been exhumed by the old masters and it was now en vogue to resent said body. So, seeing Charles Ray’s Archangel at the Met recently gave me a flood of comfort. He builds grand bodies suspended in time, deeply sensual, overtly classical. Wood, aluminum, and fiberglass turn into flesh before my eyes. And like all good sculpture, life bubbles at that magical interface between artifice and air. Rothko once said “We are for flat forms because they destroy illusion and reveal truth.” After this mid-century inheritance of flat truth, and the succeeding Pop Art movement, what did art do to the human body? Where is that recognizable vehicle of the human spirit? All the meaning we wring out of planar surface, out of ultimate truth in postmodern industry and politics, out of disintegration and detachment – all of it wilts before the elemental energy of the body. John Berger said: “We mortals know only too well that time is in our mouths, and hands, and feet, and that change is all we have to rely upon.” My changing body, with its senescence, regeneration, and constant electrical thrum, contains enough truth for me - in fact, it often feels like the only aesthetic truth.

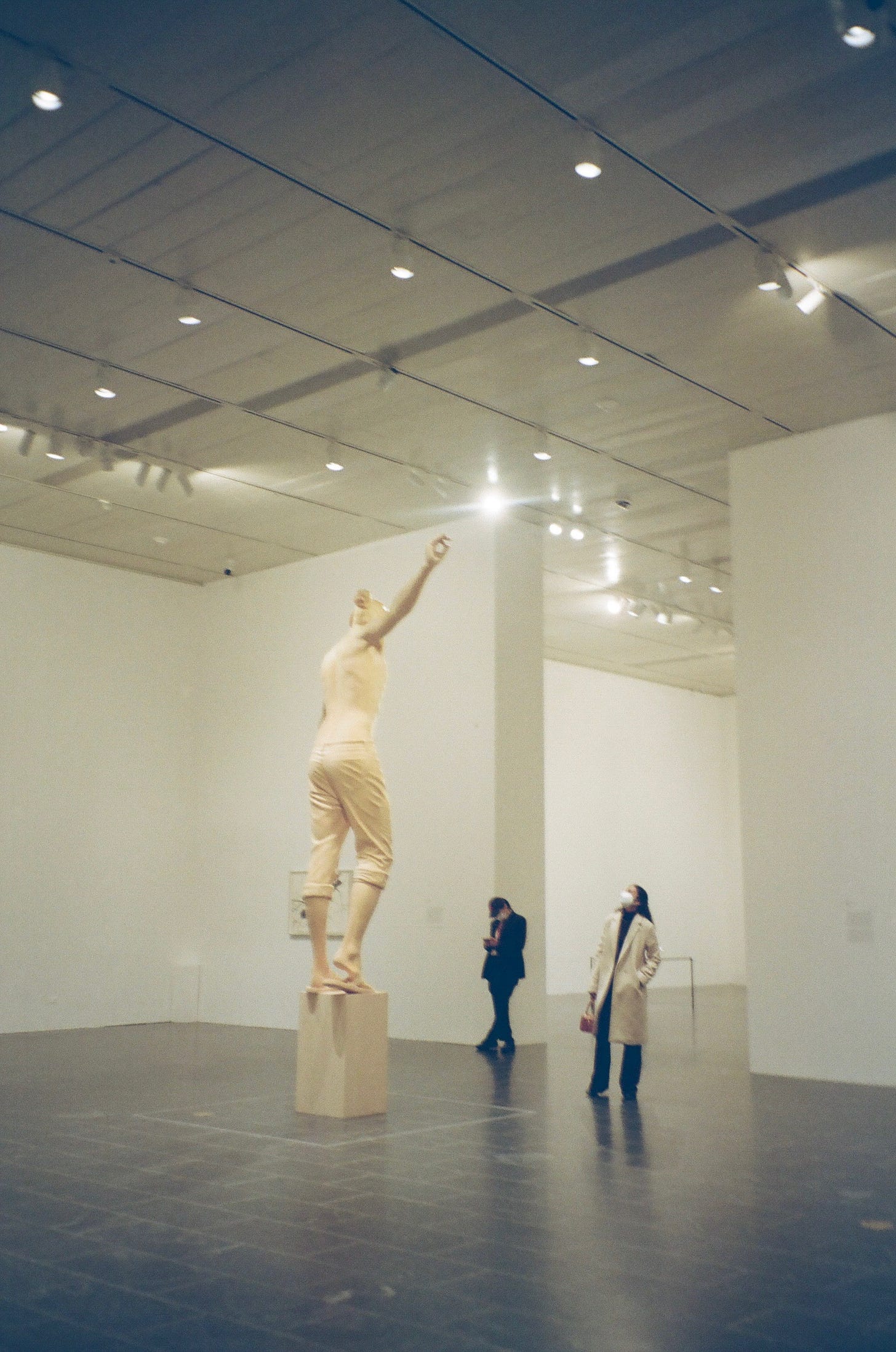

[Image description: Ray, Charles. Archangel. 2021, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image taken from this NYT article (which you should read!) that contains this excellent quote: “Each [work] has been carved with the seriousness sculptors once reserved for gods, but in forms that reflect how modernity took gods down from their pedestals.”]

Ray’s Archangel is a silent cypress giant, exciting desire, longing, fortitude, virility, longevity. I watch as the sculpture alights before my eyes, invisible wings ten times its height springing out from behind chiseled scapulae, muscle and sinew knitting new strength as gravity reminds wood hey, this is what humanity feels like. I can imagine this angel squeezing crumbling earth between his toes for the first time, or sipping cold oxygen for breath rather than flight, like Jesus before the cross. Rare, earthly delights are on offer to this trunk of cypress, this heavenly body. It is therefore on offer to us too. Charles Ray says that many viewers love the Archangel’s feet, almost adolescent in its pliancy, and I abruptly recall Polykleitos and the luscious bend of his Doryphoros’ left knee. I like my Archangel’s arms - dancing shadows of wings, set in a gladiatorial stance of such gentleness I remember why women like it when men are soft and hard together. He is young, too, a kind of young that I now envy rather than appropriate. Can the political industry of postmodern art cope with such homage to traditional figuration? Can we become poetic about the body again?

In describing John Batiste’s infectiously spiritual approach to music, a recent piece in the New York Times said that Batiste hearkens back to an older, more playful approach to jazz, one that I think silently disavows political statement. In the tradition he has inherited, there is a “mix of affability and seriousness, the deployment of humility, the insistence on values outside of an explicit political claim.” As a consumer of music and art, I tend to resent the instruction of politics. I have had enough of war, fever, perversion, and psychosomatic regression. The body is what I know, and what I have yet to discover. The success of Ray’s sculptural output suggests that the art world is changing again, as it always will. Much to the excitement of inheritors and traditionalists everywhere, the knowledge of the body is becoming sacred again.

[image description: me and archangel at the met, april 15 2022. photo by kirsten of magic hands and lovely face.]